Article 6 of the Paris Agreement: how it works and what it means for carbon markets

Reading Time: 17min

Article 6 of the Paris Agreement: how does it work and what to expect next?

As COP29 concluded on November 21, 2024, after extended negotiations, the world received significant news: nine years after the signature of the Paris Agreement at COP21, a key milestone has been achieved with a new agreement on Article 6, the pivotal framework for international collaboration on climate action.

Let’s dive into it!

25 years of COP History

The Conference of the Parties (COP) is the annual gathering of nations under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), established in 1992 to address the global challenge of climate change.

As the supreme decision-making body of the UNFCCC, the COP brings together governments, organizations, and other stakeholders to negotiate and advance international efforts to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions, adapt to climate impacts, and secure financial and technological support for climate action.

With nearly every country in the world participating, COP serves as the platform for adopting critical agreements like the Kyoto Protocol (1997) and the Paris Agreement (2015), which define the global framework for tackling climate change.

Over the past two decades, COPs have evolved from setting foundational principles to driving implementation and scaling ambition.

These meetings have become essential for monitoring progress, addressing new scientific findings, and refining climate policies to reflect emerging challenges and opportunities.

Back to the origins - Kyoto and the CDM

The Kyoto Protocol of 1997 introduced the first international carbon markets, creating mechanisms like the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), which allowed developed countries to invest in emission reduction projects in developing nations.

These projects generated Certified Emission Reductions (CERs) that could be used to meet Kyoto’s legally binding targets. While groundbreaking, the CDM faced criticism for issues like over-crediting, limited and unbalanced participation from developing countries.

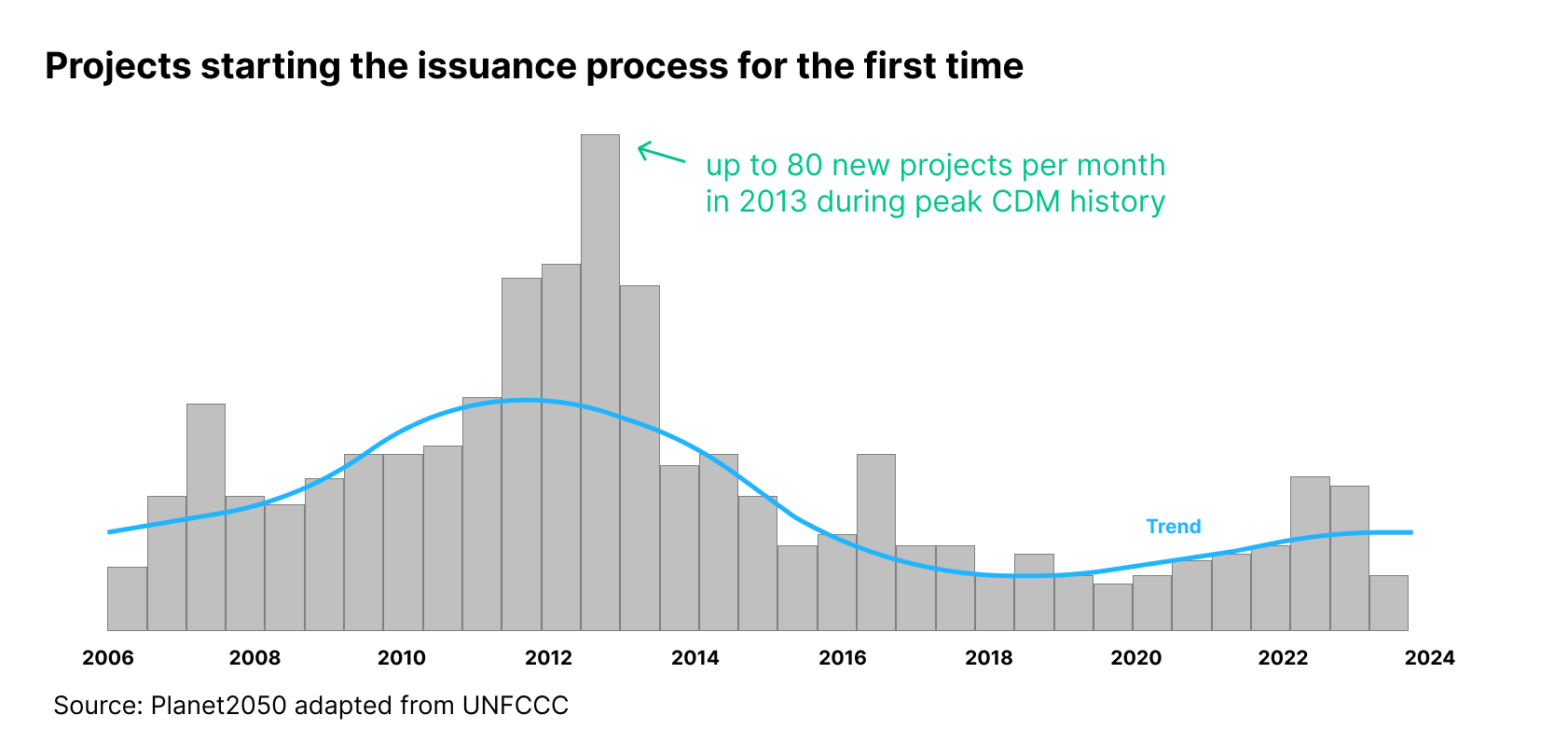

The following chart helps visualize the clear trend of CDM peak around 2010-2013 and a light rebound starting 2020-2021.

CDM Projects can involve, for example, rural electrification using solar panels or the installation of more energy-efficient boilers.

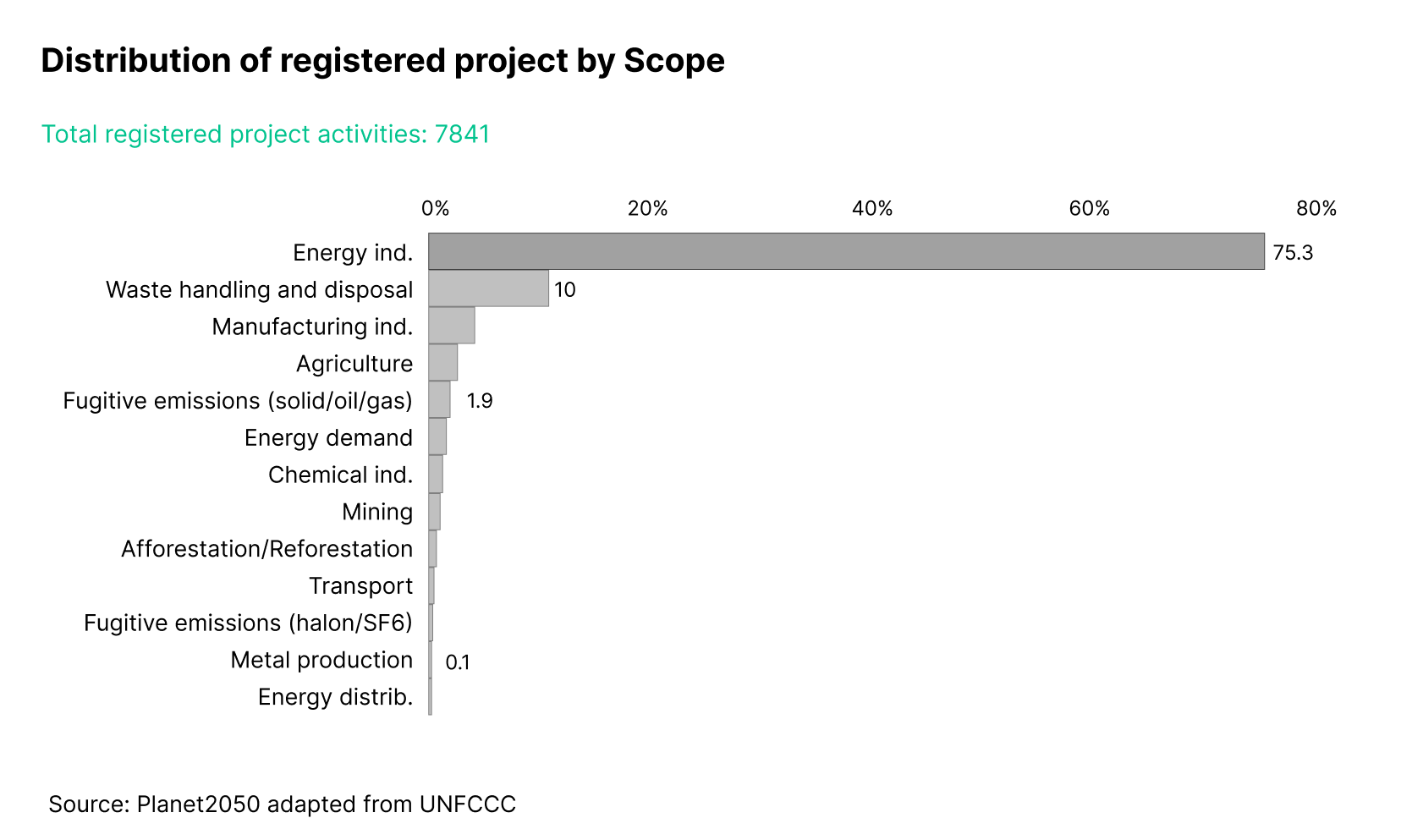

The chart below presents the distribution of projects per sector under CDM.

Structure of the Paris Agreement

The Paris Agreement (2015) replaced Kyoto’s framework with a more inclusive approach, requiring all countries—both developed (Annex-I) and developing (Non-Annex-I)—to commit to Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs).

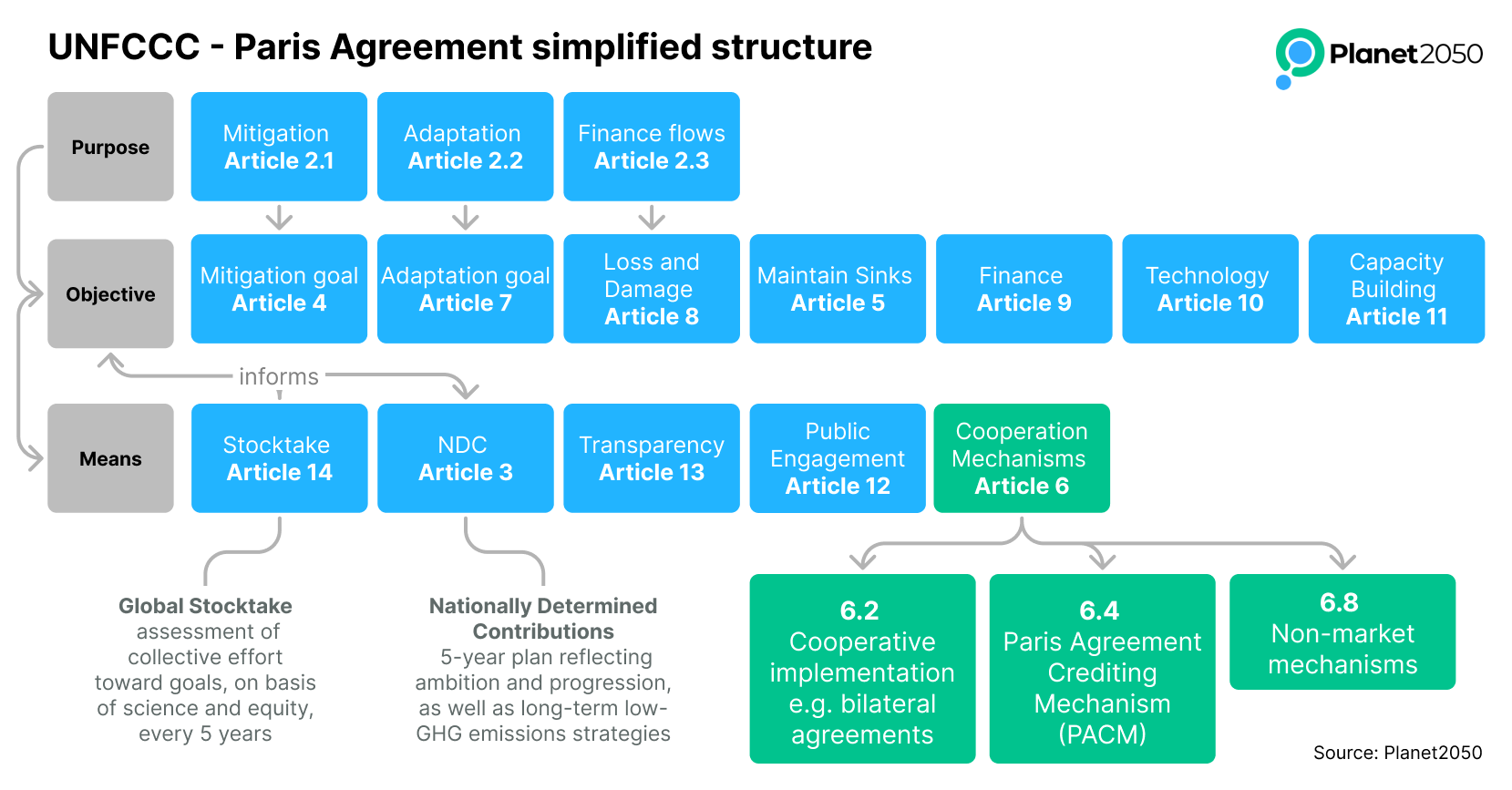

The Paris Agreement includes in total 16 introductory paragraphs and 29 articles. The following is a simplified view of the structure of the Paris Agreement with some of the main articles including Article 6 on cooperation mechanisms.

What is Article 6 and why was the COP29 in Baku seen as a key milestone?

In November 2024 during COP29 in Baku, an historical agreement was reached to operationalize Article 6, nine years after the start of the Paris Agreement.

Article 6 is a cornerstone of the Paris Agreement, providing a framework to incentivize countries and private entities to invest in climate solutions beyond their borders.

It aims to foster transparency, equity, and collaboration by enabling tools such as carbon credit trading, joint mitigation projects, and non-market partnerships.

By leveraging these innovative mechanisms, Article 6 aligns global efforts to achieve net-zero emissions and supports nations in meeting their climate goals more effectively.

Article 6 of the Paris Agreement builds on the CDM by introducing modernized mechanisms for international cooperation. It addresses past shortcomings, incorporates all participating countries, and offers both market-based and non-market approaches to enable ambitious climate action and sustainable development.

We specifically refer to three key articles (links to official texts below):

➡️ Article 6.2 which allows countries to create bilateral agreements for emissions trading, providing more flexibility.

Article 6.4 often referred to as the successor to the CDM, establishes a centralized market for trading emissions reductions with enhanced safeguards for environmental integrity.

➡️ Decision 1

➡️ Decision 2

➡️ Article 6.8 focusing on Non-Market Approaches.

Article 6.2: trading carbon credits between governments

Article 6.2 enables participating countries to collaborate bilaterally to trade carbon reductions and removals through the transfer of credits known as Internationally Transferrable Mitigation Outcomes (ITMOs) to achieve their climate targets known as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs).

Article 6.2 provides a significant degree of autonomy to the countries involved. They are free to choose and steer the type of emission units that can be traded, design their own policies, agreements and registries. Some may develop their own methodologies, or follow international voluntary ones from existing carbon standards.

During the COP27 in 2022 taking place in Sharm El-Sheikh, Ghana became the first country to authorize the export of ITMOs. Since then, other nations have followed such as Switzerland, Japan, Singapore, Sweden.

Countries involved in Article 6.2 will also need to provide Letters of Authorization (LoA), fulfill reporting requirements, and then monitor and verify the projects.

Article 6.2 guidance requires countries to report on how they make use of carbon markets to help achieve their Paris Agreement targets (NDCs). Only after the first monitoring cycle that the first issuance and transfer of credits can take place.

In terms of registry, countries will either develop their own national registries, use a third-party registry, or use the Article 6.2 international registry.

The International Emissions Trading Association (IETA) provides a tracker for countries which have already concluded bi-lateral Article 6.2 agreements.

UNEP is also updating similar information regarding the Article 6 pipeline in this page.

Agreements between countries are usually done in the form of a Memorandum of Understanding (MoUs) highlighting cooperation areas and objectives.

Some partnerships have already been very active with multiple projects registered or in development.

Countries will soon have several options of template available to write their LoA. On November 14th at COP29, the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) of the World Bank Group released its own LoA template to facilitate guarantee issuance in support of private investors engaged in Article 6 carbon markets.

About ITMO Buyers

ITMO buyers are usually government themselves but it can also be companies directly. For example in Singapore, companies subject to the carbon tax can offset up to 5% of their taxable emissions and can use high-quality international carbon credits, including those aligned with Article 6 of the Paris Agreement.

To facilitate this, Singapore has established the International Carbon Credit (ICC) Framework, which sets the eligibility criteria for carbon credits that can be used for tax offsets.

Singapore has signed Implementation Agreements with Ghana, Papua New Guinea and more than 20 other countries enabling the generation and transfer of Article 6-compliant carbon credits.

The case of Switzerland

Switzerland aims to halve its greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 compared to 1990 levels. A significant portion of this reduction will be achieved through international cooperation under Article 6 mechanisms.

In this context, the Klik Foundation is the responsibly entity in charge of the sourcing and development of Article 6.2 projects. The Foundation is also acting as the carbon offset grouping of the Swiss motor fuel importers, mandated under the Swiss CO₂ Act to offset parts of the carbon emissions generated by the use of motor fuels in Switzerland.

At COP29, Klik reported on its progress:

222 project proposals received to data since 2019

130 rejected or withdrawn

92 currently under consideration or implementation, among which 33 under development and 7 for which a Mitigation Outcome Purchase Agreement (MOPA) has been signed.

Most of the mitigation activities under consideration for Klik are in Ghana, in addition to Latin America, Caribbean and Thailand.

Ms. Vicky Janssens (KliK Foundation) and speakers at COP29

Unlike other Article 6.2 participants, Switzerland defined only non-nature-based projects as eligible. Mitigation activities under development include:

Electric Mobility: E-buses and e-taxis in Senegal, deploying e-vehicles and building up charging infrastructure in Dominica, e-buses and e-trucks in Thailand, Chile, Uruguay.

Green cooling: Transitioning to high efficiency AC units with low GHG emitting refrigerants in Ghana and ensuring sustainable end-of-life (EoL) disposal.

Solar PV programs: rooftop PV installations on residential/commercial buildings in Ghana and Morocco. Solar farms in Peru.

Waste management: Establishing recycling points, composting facilities, and landfill gas collection in Senegal to create a streamlined waste management system.

Improved cooking solutions: supporting the dissemination of efficient cooking solutions, including electric cooking, in Ghana, Malawi, Senegal, Peru.

Alternate Wetting and Drying (AWD): introducing water management techniques to farmers, in order to reduce methane emissions in Thailand.

Biogas: Ghana, Malawi, Uruguay, Georgia

Article 6.4: a global carbon-crediting program governed by the UN

Guided by the Supervisory Body of the UNFCCC, Article 6.4 introduces a centralised, global carbon market mechanism called the "Paris Agreement Crediting Mechanism" (PACM), in a manner similar to CDM under the Kyoto Protocol.

In the PACM, project developers can perform emission reduction or removal activities and register these with the Article 6.4 Supervisory Body.

If you are familiar with voluntary carbon crediting programs, you can visualise more or less a similar model with Article 6.4’s governance structure, methodology, requirements for Monitoring, Reporting and Verification (MRV), and a registry system.

"For example, through this mechanism a company in one country can reduce emissions in that country and have those reductions credited, so that it can sell them to another company in another country. That second company may use them for complying with its own emission reduction obligations or to help it meet net-zero targets." (UNFCCC)

Credits issued are called A6.4 Emission Reductions (A6.4ERs) or also Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes (ITMOs), depending on whether they are authorized by the host country for use toward NDCs or for the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA), and have been subject to corresponding adjustments. Emission reductions under this mechanism can be claimed by either the buyer or the host country, but not both.

Methodologies approved for Article 6.4

Unlike in Article 6.2 where countries have flexibility to use different methodologies, projects under Article 6.4 will have to follow a rigorous process and authorized methodologies.

During a pre-COP29 meeting in October 2024, the Article 6.4 Supervisory Body had already approved two standards:

Standard on methodology requirements: Requirements for developing and assessing projects under the Paris Agreement Crediting Mechanism.

Standard on activities involving removals: Rules for projects that remove greenhouse gases from the atmosphere.

Project participants, host countries and other stakeholders will have the possibilities to propose new methodologies under Article 6.4 which will be developed following the guidance in place.

What will happen with CDM methodologies?

As outlined, the PACM framework is updating methodologies, revising protocols, and excluding outdated approaches to ensure accuracy and effectiveness.

Five methodologies from the CDM era are currently being evaluated for their potential incorporation into the new mechanism. These methodologies cover projects in areas such as renewable energy, energy efficiency, and landfill gas management. Starting in 2026, they are expected to comply fully with Article 6 guidelines.

A key decision facilitates the transition of substantial volumes of old CDM credits into the new PACM, provided they meet the updated, stringent criteria for removals.

Meanwhile, what happens to projects currently in their CDM crediting period?

Existing CDM projects can continue using the same CDM methodologies until either 31 December 2025 or the end of their current crediting period, whichever is sooner.

Projects registered on or after 1 January 2013 can use their Certified Emission Reductions (CERs) towards meeting the first cycle of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), which generally concludes in 2030.

Projects under the Kyoto Protocol’s Joint Implementation mechanism (ERUs) are not eligible under Article 6.

Future of CDM

CDM is approaching its phase-out and can no longer accept new project registrations, renew crediting periods, or issue CERs for emission reductions beyond 31 December 2020.

The remaining funds are likely to be redirected to support the Article 6.4 mechanism in the future, although this remains a contentious issue with no definitive decision as of June 2024.

Authorization Mechanism: How Corresponding Adjustments work

Introduced by Article 6.3, a corresponding adjustment is necessary under Articles 6.2 and 6.4 for all units approved by the host country, including those originating from sectors not covered by an NDC.

The concept aims to prevent double counting by ensuring that emissions reductions are assigned to only one entity or country.

When a credit is transferred internationally, the host country deducts it from its own records, while the buyer incorporates it into their climate targets.

This approach ensures that emissions reductions are counted only once, maintaining accuracy and avoiding inflated mitigation outcomes.

Corresponding adjustments addressing double counting

Source: The Nature Conservancy, 2023

On the contrary, units that are not authorised for the use towards NDCs and thus exempt from Corresponding Adjustments were called ‘Mitigation contributions’.

Source: The Nature Conservancy, 2023

The text defines these ‘non-authorised units’ (Mitigation contributions) to be intended for use towards ‘other purposes’.

These purposes have been defined as results-based climate finance, domestic mitigation pricing schemes, or domestic price-based measures, to support the host country's emission reduction efforts.

This, in the context of the voluntary carbon markets, translates to be used towards voluntary emissions pledges.

Loosely, the definition accounts as a compromise addressing differing national perspectives on Article 6. Consequently, some experts view Article 6 markets as hybrid or integrated markets.

As such, the global voluntary carbon markets, regulated cap-and-trade systems, and Article 6 mechanisms are progressively aligning, enhancing interoperability and increasing trade opportunities.

Hybrid carbon markets

One of the best examples is the Australian Government’s Carbon Credit Unit (ACCU) system. Carbon abatement projects play a dual role in Australia’s climate strategy.

They can contribute to voluntary offset claims for businesses aiming to demonstrate environmental responsibility or fulfill compliance requirements under the Safeguard Mechanism.

This mechanism mandates the country’s largest emitters to collectively cut emissions by 205 million tonnes by 2030, creating a robust framework that bridges voluntary actions with regulatory obligations to achieve significant emissions reductions.

Another example is the label bas-carbone government-led scheme by France, which can only be used for voluntary purposes.

Article 6.8: Non-market approaches

Non-market approaches (NMA) under Article 6.8 allows countries to support each other’s climate mitigation efforts without trading carbon credits. Article 6.8 will establish a centralized platform (the web-based NMA Platform is under development) for countries to submit their planned mitigation projects and indicate where they need support.

The Glasgow Committee on NMA reached a consensus on 15th Nov at COP 29, on a draft decision for the roadmap of the Article 6.8 work programme. Spanning over the next two years, the roadmap focuses on enhancing collaboration among Parties, non-state actors, and other stakeholders.

The framework adopted to steer the objectives and define scope/ focus of such activities is dubbed the Work Programme.

Post-COP29 carbon market development

The results of COP29 have played a pivotal role in shaping the direction of carbon markets, closely linking them with voluntary carbon market frameworks and efforts to achieve net-zero and decarbonization goals on both national and personal scales. Looking ahead, it is essential to focus on several critical elements to ensure these mechanisms are implemented effectively.

Advancement in Bilateral Carbon Trading

Article 6.2 has already started and is poised to take off significantly with countries signing new ITMO agreements. As of November 7, 2024, 91 bilateral agreements have been established among 56 nations, indicating a robust commitment to cooperative climate action. Full disclosure of information from the host countries is critical to the success of Technical Expert Reviews in accounting for additionality and transparency.

Operationalizing Article 6.4: Progress and Challenges

Article 6.4 signals great momentum but will take time to operationalise considering technical difficulties a.o. in registries, transitioning of existing CDM methodologies, interoperability of VCM schemes with Article 6.4., etc.

Growth of Carbon Markets Convergence

The Compliance markets will grow more and establish themselves in the coming years without denting the growth of the Voluntary Carbon Market (VCM). As seen from the establishment of the EU’s Carbon Removal Certification Framework, which keeps a focus on the voluntary market as a key application. These markets will exist parallelly with steps towards more convergence into a unified carbon market in full swing after 2030.

Role of NDCs in defining Carbon Market Integration in National Targets

The February 2025 deadline for updated Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) will give a clear picture of how far countries have come in tackling climate goals. It’s a chance to see if the world is truly on track to meet the increasingly tough emissions targets for 2035.

What will be particularly interesting is how many countries plan to use Article 6 mechanisms as part of their strategy. This will show how global carbon markets are shaping up and how nations are collaborating to hit their goals.

Mobilizing Climate Finance for Developing Nations

A big question is how the pledged $300 billion a year for climate action in developing countries—starting in 2035—will begin to take shape. Will the funds flow effectively, and will they reach the communities that need them most? These updates will reveal not just progress but also the level of commitment to delivering real, lasting change.

Carbon Market decisions to watch for in 2025

The Supervisory Body, also known as "SBM", has released its work plan for 2025. It aims to finalise all work related to requirements for methodologies and for activities involving removals, as well as to revise the methodologies and tools of the Clean Development Mechanism.

It will also continue the work on the PACM registry requirements and the modalities of its operations.

The work plan highlights key SBM activities:

Review regulations, also consider the possibility of incorporating Know Your Customer (KYC) process within article 6.4 mechanism

Develop Sustainable Development Tool in context of activity types

Develop registry requirements and modalities for operations of Article 6.4 mechanism

Provide guidance on transitioning cases register registration and issuances

Requirements for methodologies involving removals

Review of CDM methodologies and tools

Implement capacity building program

COP 30 Highlight: Spotlight on nature

Brazil has signaled its intent to establish mechanisms at COP30 aimed at forest conservation. The "Tropical Forests Forever Facility" (TFFF), introduced at COP28, is designed to provide financial incentives to countries for preserving tropical forests, with implementation anticipated by COP30.

Concurrently, the G20 is addressing "debt-for-nature" initiatives, which allow countries to restructure debt in exchange for commitments to environmental conservation. This approach aims to alleviate financial burdens while promoting ecological preservation.

________

Don't miss our on key trends and developments in the carbon markets with our monthly Market Briefs. Sign up here to make sure you receive them!