Planet2050's Contribution to the SBTi's Scope 3 consultation

Reading Time: 17min

Planet2050 has participated in the SBTi's public consultation on Scope 3 based on a discussion paper published in July 2024. This came after a period of market confusion and debates on the role of Environmental Attribute Certificates (EACs) and offsets in the decarbonization of value chains.

The new era of Net Zero Frameworks

While our Planet is about to breach seven out of nine planetary boundaries, the international community is increasingly looking for solutions to restore the stability of the planet’s life-support functions, with special focus to limiting the increase in average global temperatures to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels as set up in the Paris Agreement.

Globally, companies have a key role to play to contribute to emission reductions by redefining how we produce and consume on a global scale, encourage the switch to low-carbon energies and develop more sustainable practices within and beyond value chains.

This is why more and more companies are setting emission reduction targets and developing strategies using available Net Zero frameworks such as the Sciences Based Target Initiative (SBTi), which 9015 organizations are already adhering to.

These frameworks usually provide guidance on aligning reduction pathways to the Paris Agreement objectives, properly accounting for emissions and creating inventories, and defining intermediate and 2050 targets. Furthermore, they set out general guidance on how to use market-based mechanisms such as carbon credits and additional contributions as part of Net Zero strategies.

In this context, a topic that has sparked heavy debate recently is SBTi’s position towards the application of EACs regarding the reduction of indirect value chain emissions (Scope 3).

Did you miss the debate or wonder what is Planet2050’s stance? Read further!

What are Scope 3 emissions again?

In case you are not familiar with the concept:

Scope 1 emissions are direct emissions from owned or controlled sources (i.e. company facilities and vehicles)

Scope 2 emissions are indirect emissions that occur in the generation of purchased energy.

Scope 3 emissions are "all indirect emissions that occur in the value chain of the reporting company, including both upstream and downstream emissions” (GHG Protocol)

Think about products bought from suppliers, leased assets, transportation of products and associated fuels, business travels, but also the use of products sold and emissions embedded in investments.

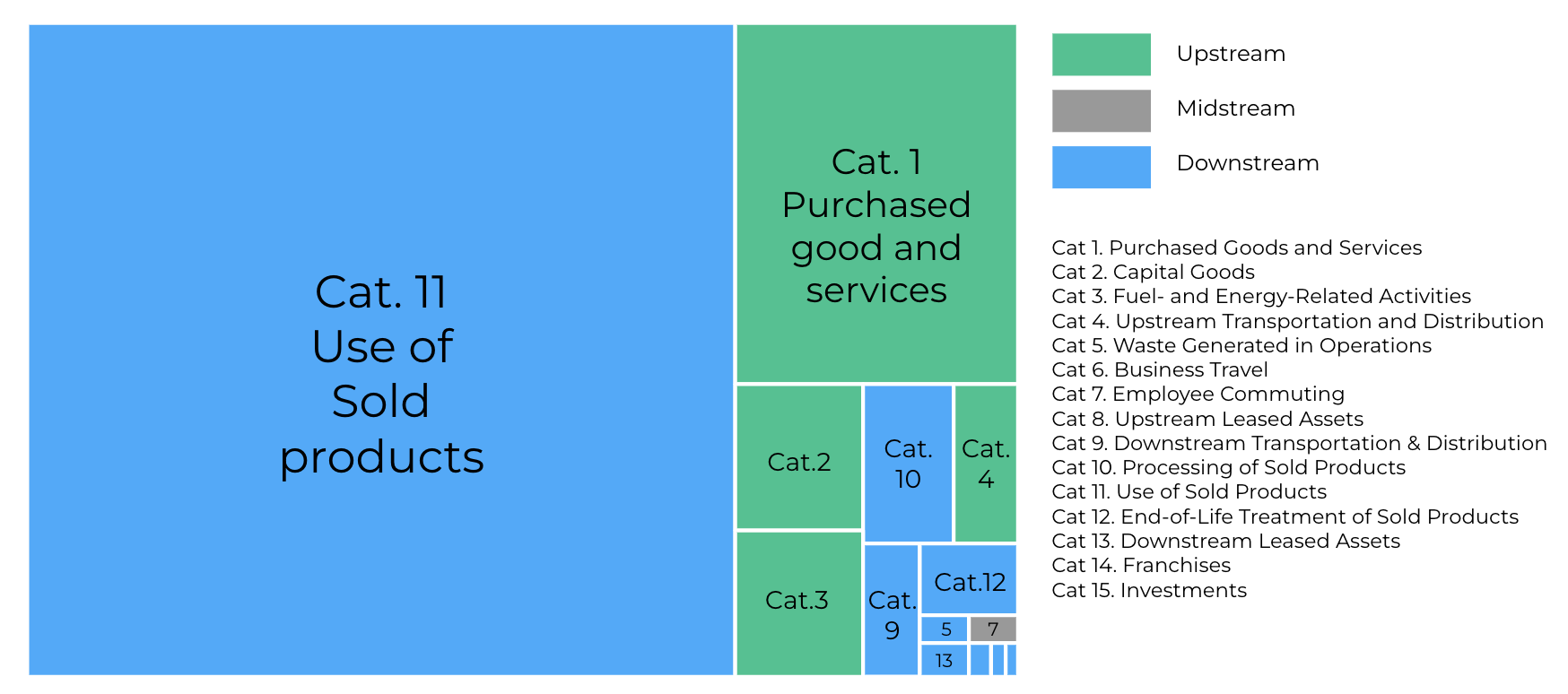

GHG Protocol defines 15 different categories of Scope 3 emissions and present their relative importance within Scope 3 based on self-reported emissions data publicly disclosed to CDP:

Figure 1: Scope 3 emissions by category, excluding category 15

Figure 1: Scope 3 emissions by category, excluding category 15

(source: adapted from SBTi based on self-reported emissions data publicly disclosed to CDP)

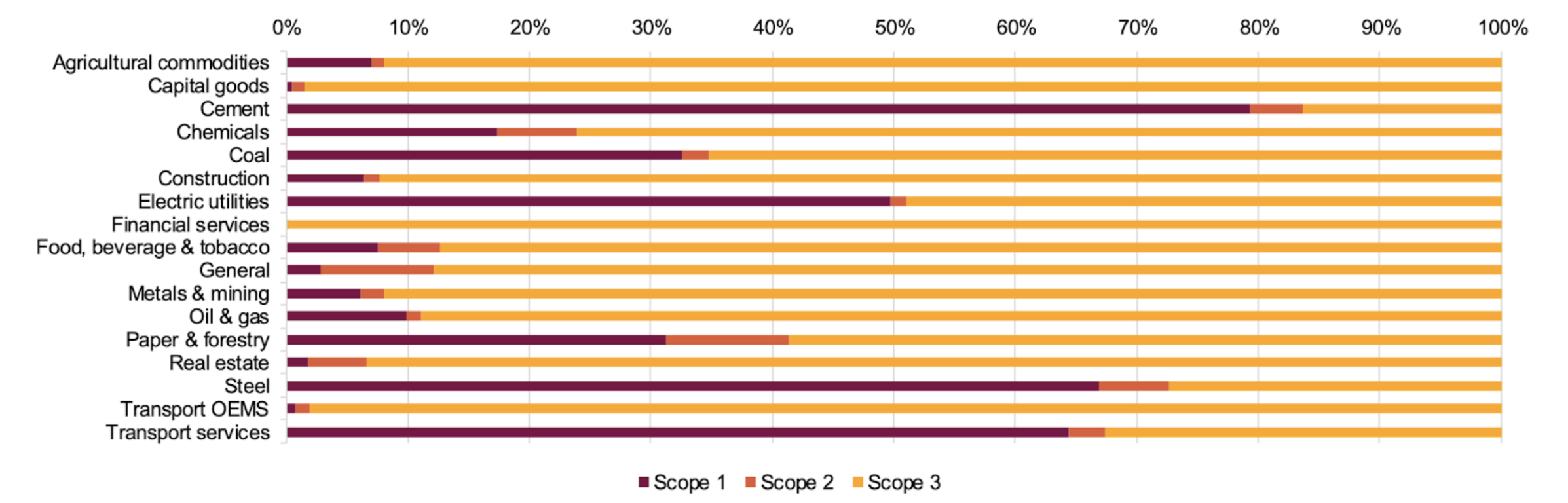

In most sectors, Scope 3 emissions represent the largest share of emissions within a company’s value chain – being on average 11.4 times higher than direct emissions (Scope 1).

The Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) found that in 7 out of 17 sectors, Scope 3 emissions represent more than 90% of overall value chain emissions (see fig 2).

Figure 2: Scope 1, 2, and 3 Emissions by Sector (source: CDP, 2024)

Figure 2: Scope 1, 2, and 3 Emissions by Sector (source: CDP, 2024)

How are Scope 3 emissions included in emission reduction target setting based on the SBTi standard?

A growing number of companies are adhering to Net Zero frameworks such as SBTi, committing to reduce emissions in line with reduction pathways to limit anthropogenic climate change to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.

According to current data from SBTi, by the end of 2023 companies with science-based targets (SBTs) or commitments made up 39% of the global economy by market capitalization.

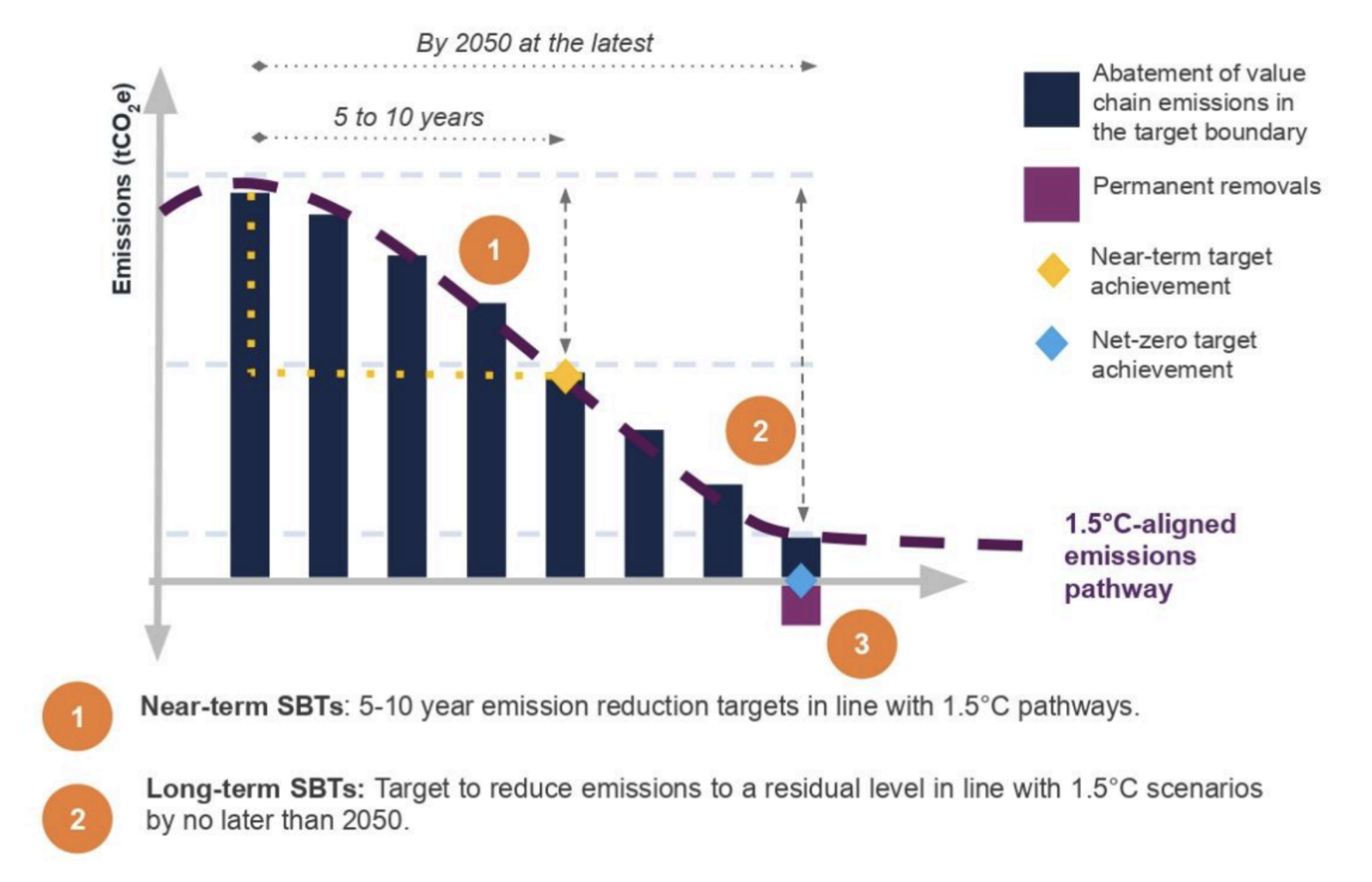

Recognizing the urgency of achieving Net-Zero by 2050, the SBTi mandates that long-term company targets cover and reduce at least 90% of emissions across all Scopes, aligned with a 1.5ºC warming scenario, except for sectors forestry, land use, and agriculture, where the threshold is 72%.

Under these requirements, only companies with a substantial Scope 3 footprint (at least 40% of the total company carbon footprint) need to set targets for their value chain emissions. For SMEs, Scope 3 targets remain voluntary for now.

As of September 2024, 6158 companies and financial institutions have emission reduction targets validated by SBTi. Approximately 97% of them included Scope 3 emissions in their targets.

How are companies addressing Scope 3 and where do they stand?

Companies start to assess Scope 3 emissions, typically using a combination of supplier engagement tools and surveys, spend-based models, and life cycle assessment to gather activity data and estimate emissions across the value chain.

Here, the SBTi recommends prioritizing high-impact categories through screening and hotspot analysis, using industry-accepted emission factors, and collecting primary data where feasible. Continuous improvement, transparency, and alignment with GHG Protocol standards are essential for ensuring accuracy and setting SBTs.

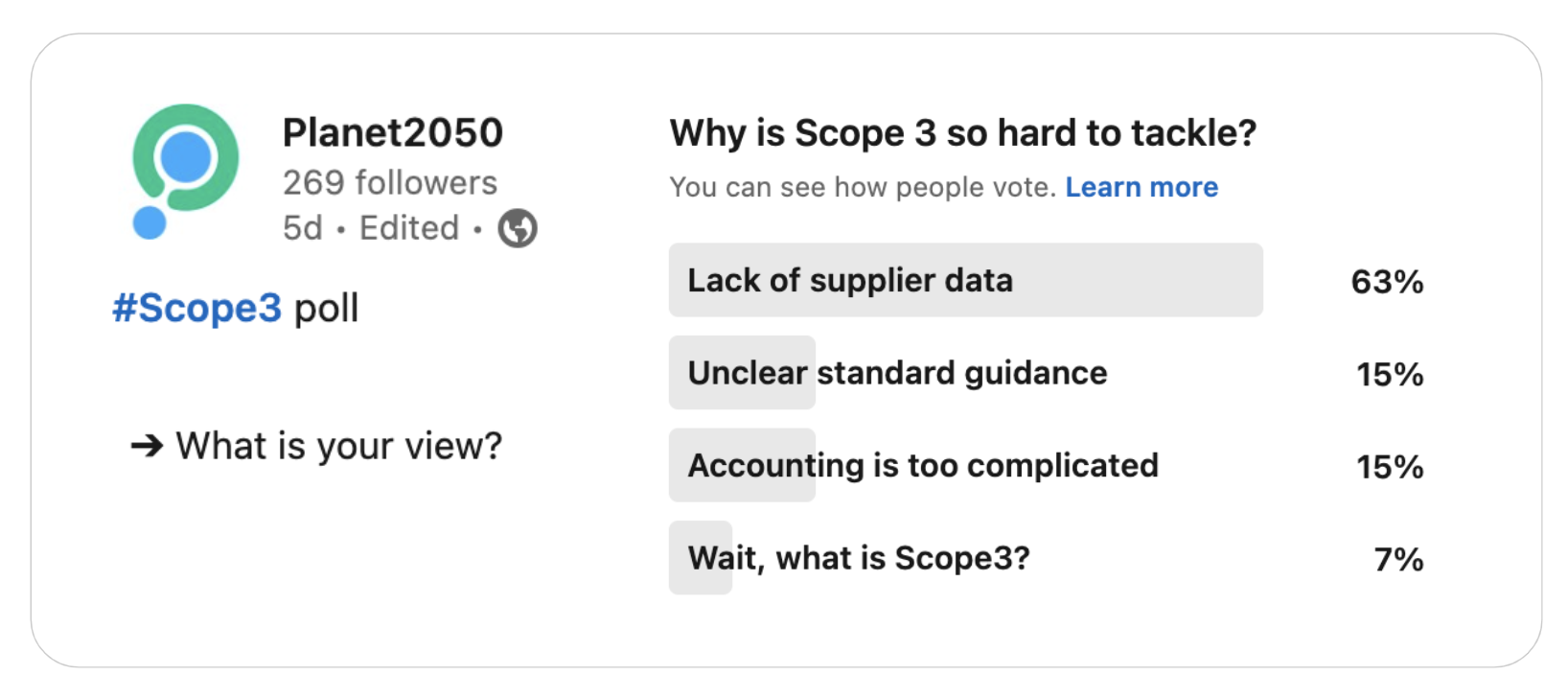

Although guidance exists and selected companies are showing best practices, as highlighted in the UN Global Compact’s Scope 3 Data Collection Case Studies report, assessing Scope 3 and engaging with suppliers remains the largest challenge.

According to the World Wilde Fund for Nature (WWF), companies are finding it difficult to influence suppliers, absorb the costs of decarbonization, and monitor progress toward their targets due to insufficient primary data. Data collection can be difficult due to the complexity and variability of supply chains, lack of transparency, and inconsistent reporting practices especially in supply chains with limited options for influence from companies.

This is also what appeared in our recent LinkedIn poll focusing on obstacles to address Scope 3 (fig 3).

Figure 3: Planet2050 linkedIn poll on Scope 3.

Figure 3: Planet2050 linkedIn poll on Scope 3.

Beyond data collection, finding effective Scope 3 emissions reduction options requires collaboration, investment, and alignment with diverse stakeholders who may have different priorities and capabilities especially due to the complexity and global nature of supply chains.

Sectors like aviation or steel have only few affordable options for direct emissions reductions. Across industries, companies also face challenges procuring renewable energy in regions where political will or capacity to transform national energy systems is lacking.

As a result, growing voices alert on the risks of missing targets related to Scope 3, and demand more flexibility in ways companies can design their strategies.

Under-delivery of Scope 3 within Net-Zero commitments

Analyzing European companies, Capgemini and CDP highlighted that most are overlooking critical Scope 3 emissions hotspots. In 2022, 92% of disclosed emissions were Scope 3, of which only 37% were addressed by decarbonization efforts.

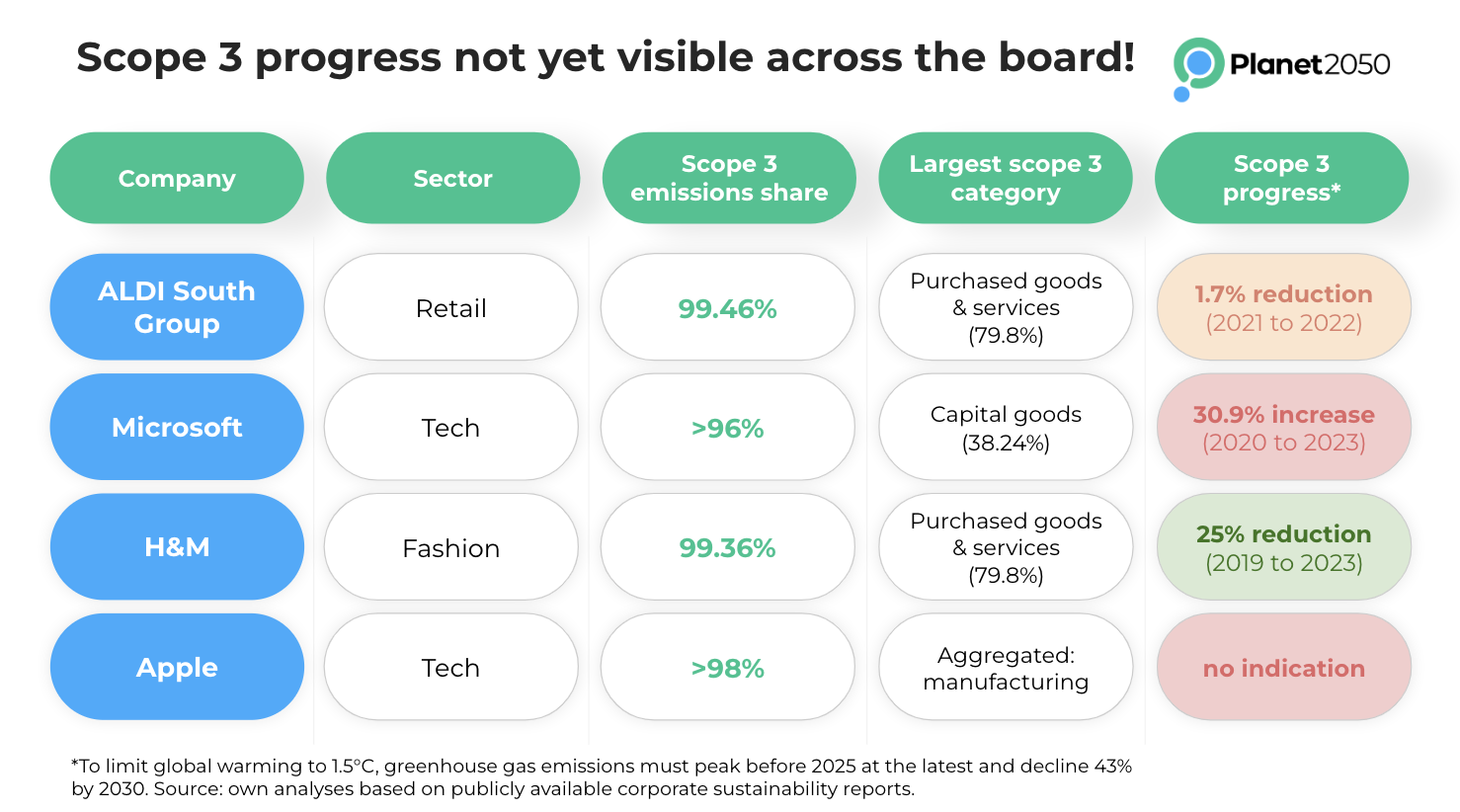

We illustrate the reality of Scope 3 with example from four companies selected by Planet2050:

Table 1: Industry leading companies and their Scope 3 footprint and progress (source: own analysis based on companies recent sustainability and progress reports).

Table 1: Industry leading companies and their Scope 3 footprint and progress (source: own analysis based on companies recent sustainability and progress reports).

A recent analysis from IETA and AlliedOffsets suggests that the emissions gap between companies’ Scope 3 targets and their current emissions is currently around 1.4 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent, projected to rise to over 7 GtCO2e by 2030.

Despite challenges and lacking progress, pressure is mounting for many companies to show actual improvements. An evolving ecosystem for sustainability reporting requires more and more companies to report on their Scope 3 emissions on a legislative basis. Examples are the EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and the recent Climate Corporate Data Accountability Act in California.

As companies navigate the challenge of decarbonizing complex value chains, a debate has emerged around the suitability of market-based mechanisms, particularly the flexibility in setting near-term Scope 3 goals and the use of Environmental Attribute Certificates (EACs), to reach emission reduction targets.

Points of discussion from SBTI’s consultation and paper

SBTi’s paper from July 2024 discusses key concepts for companies to set Scope 3 targets aligned with the Paris Agreement's 1.5 °C objective. Furthermore, it expresses SBTi’s ambition to examine the role that market mechanisms such as Environmental Attribute Certificates (EACs) might play for companies to make progress on reduction pathways within and beyond value chains.

1/ Alignment targets vs. reduction targets

SBTi provides a framework for companies to set their general emission reduction targets including scope 3, as well as different methods to address these emissions ranging from “contraction of scope 3 absolute emissions, to a reduction in scope 3 emissions intensity, and to addressing value chain emissions by driving the adoption of science-based targets among their suppliers or customers” (SBTi, p. 18).

SBTi now also introduces “alignment targets”, a new concept focus on aligning a company’s emission reduction pathway with global climate goals and sector-specific carbon budgets.

For instance, a construction company might set short-term goals based on the percentage of the procurement of near-zero emission steel, rather than solely focusing on a general emissions reduction from a baseline year.

It is being discussed whether these should become part of standard procedure under SBTi. The proposal emphasizes the need for companies to take immediate action and focus on specific sector transitions instead of just overall GHG metrics.

Our perspective:

We welcome the new approach as it aims to tackle some of the limitations of the current SBTi standards by recognizing that companies have different responsibilities and circumstances.

However, emission reduction targets remain essential for major corporations to ensure accountability regarding the long-term goal to achieve near-zero emissions across all sectors.

Setting alignment targets doesn’t guarantee that a company’s overall business model will be compatible with 1.5°C goals. Consider a manufacturing company that sets alignment targets to reduce emissions from its production processes by increasing energy efficiency and using renewable energy sources. If the company simultaneously derives a major source of its revenue from sourcing materials with high carbon footprints, the alignment targets alone would not be sufficient to ensure 1.5°C compatibility.

Therefore, we believe that maintaining overall GHG emission reduction targets alongside alignment targets is crucial to ensure that all aspects of a business adhere to climate objectives.

2/ Thresholds for incorporating Scope 3 emissions in target setting

In the current SBTi Corporate Net Zero Standard (v1.2), only companies with a significant Scope 3 footprint (40% or more of their total emissions) are required to set reduction targets that include their upstream and downstream activities. Furthermore, the standard requires companies to address at least 67% of their Scope 3 emissions in their interim targets, while companies can choose which ones to include.

Our perspective:

Percentage thresholds like 67% may lead companies to stop once they meet the minimum requirement, missing chances to reduce the most impactful emissions. This can create a misleading sense of progress.

Instead, SBTi could require companies to set targets that cover the most significant emission sources in their sector and to justify those ones not addressed.

This approach would encourage meaningful reductions, improve transparency, promote best practices across sectors, and better align with SBTs and future regulations. Support could be given to companies by defining critical processes and production steps that matter most for climate goals.

3/ Integration of market mechanisms like EACs into corporate decarbonization

What are Environmental Attribute Certificates (EACs)?

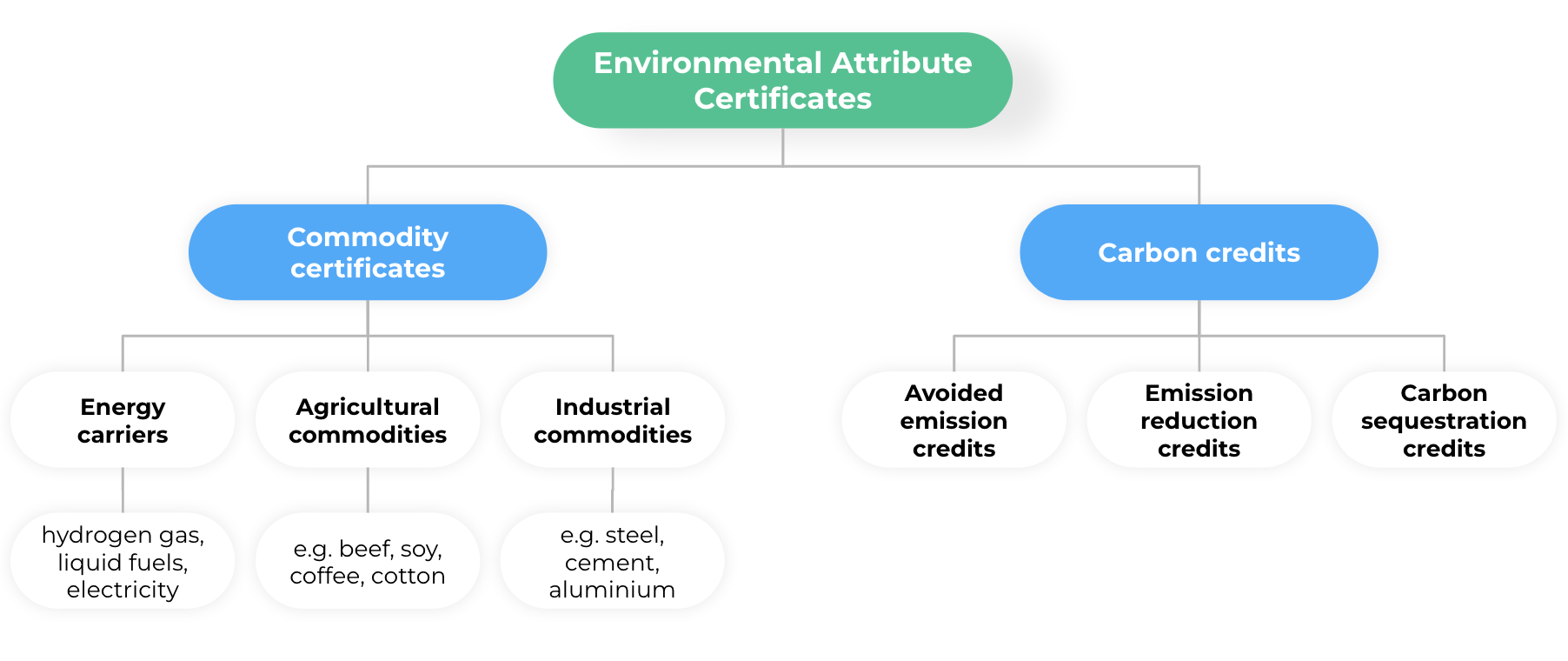

Environmental Attribute Certificates (EACs) are instruments that certify and communicate the environmental benefits of specific activities or commodities.

Showing that companies have met specific environmental standards or environmental criteria, these certificates help companies back up their sustainability claims, comply with voluntary or regulatory schemes, and improve transparency in their value chains.

EACs enabling climate-related claims generally fall into two categories: commodity certificates and carbon credits (fig 4).

Commodity certificates provide verified information about the sustainability of how various products are made. They deliver verified data on the environmental and/or social performance of a commodity in conformance with a specific sustainability standard.

In contrast, carbon credits are tradable units representing specific amounts of greenhouse gas emissions reduced or avoided through different kinds of projects or interventions. Usually quantified in tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent these credits are verified and certified by established standards.

Carbon credits can result from various mitigation activities that avoid emissions, reduce them, remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, or conserve existing carbon stocks.

Figure 4: Overview of environmental attribute certificates commonly used to substantiate climate-related claims (source: adapted from SBTi, 2024).

Figure 4: Overview of environmental attribute certificates commonly used to substantiate climate-related claims (source: adapted from SBTi, 2024).

The SBTi explicitly rules out carbon credits from activities outside the value chain to be counted as emission reductions when measuring progress towards a company’s near-term or long-term SBTs.

However, EACs (including carbon credits) are part of SBTi’s long term strategy for companies to enable Net-Zero on a global scale. While a Net-Zero target requires companies to focus on their own emission reduction efforts, the transition takes time and residual, hard-to-abate emissions usually remain.

To achieve Net-zero emissions on a global scale, these residual emissions must be neutralized. This refers to the actions companies take to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store it permanently to balance out any emissions that remain after companies achieve their long-term SBTs.

That means that any emissions not included in their main targets must also be countered by removing an equivalent amount of carbon from the atmosphere (fig.5).

Figure 5: Abatement of value chain emissions and permanent removals (source: SBTi p. 13)

Figure 5: Abatement of value chain emissions and permanent removals (source: SBTi p. 13)

The climate community agrees that the Carbon Dioxide Removals (CDR) sector must secure significant investments in the near-term already (see for instance IPCC AR6), in order to be significantly mature to capture the needed amount of residual emissions once companies reach their long-term targets. Many argue that the most efficient way to achieve this is through carbon credits especially Carbon Dioxide Removals (CDRs).

Beyond Value Chain Mitigation

Beyond residual emissions, SBTi encourages companies to take action or make investments beyond their own value chains to mitigate GHG emissions (Beyond Value Chain Mitigation – BVCM). This could be regular support to initiatives and solutions that provide quantifiable benefits to climate, and potentially co-benefits for people and nature. EACs are a key instrument, among others, in financing BVCM and taking climate action today.

In the Scope 3 discussion paper, SBTi explores options how EACs (both commodity certificates and carbon credits) from mitigation activities within the value chain could be applied to substantiate emission reduction claims. Furthermore, the paper discusses the use of carbon credits to compensate residual emissions and to support BVCM.

3.1/ Commodity certificates in cases of limited value chain traceability

In certain value chains, products can individually be tracked based on their own sustainability attributes. Here, traceability is given based on identity preservation and physical segregation.

However this is not always possible, for example with commodities, crops, low-carbon fuels or energy carriers. In such cases, sustainability certification schemes introduce chains of custody which allow to unbundle the EAC from the physical flow of products.

It is easy to understand this concept with Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs), where renewable- and fossil-sourced electrons cannot be physically segregated in a single electrical grid. In this case, holding the certificate is the only mechanism to substantiate a claim.

In an exemplary case, BCG is using Sustainable Aviation Fuel certificates (SAFc) from a so-called “book-and-claim” registry to compensate for the Scope 3 emissions associated with the travel of its staff members.

“BCG's purchase of SAF certificates allows the company to make a greenhouse gas reduction claim on climate disclosures, while the physical SAF flows to an aircraft operator. The integrity of the transaction is digitally tracked and third-party verified through a ledger system chain of custody model known as Book & Claim”

Our perspective:

We view commodity certificates as potentially efficient tools to track environmental efforts in the supply chain. They could help create a shared definition for 1.5°C alignment of purchased goods and services. They could further certify products based on a clear and standardized definition of what aligns with the 1.5°C target. SBTi could ensure that these definitions are developed scientifically and independently.

Commodity certificates can help communicate about environmental characteristics of the products companies buy, as long as there is a reliable system tracking these products from their source to the buyer.

When considering the use of commodity certificates in value chain activities, SBTi should establish clear criteria for which certificates are acceptable based on the sector, product, or production process.

Furthermore, a clear definition of what qualifies as "value chain” is much needed, as in many cases boundaries can be blurry.

To prevent double counting or misallocation of these certificates, secure traceability and accounting mechanisms should be promoted. Certificates should offer real, data-backed tracking and verification to add integrity to the environmental characteristics of products companies buy. Blockchain-based traceability systems offer solutions here.

We suggest incorporating the concept of a "supply shed”, which provides flexibility for companies to make impact claims and source certificates as long as within a specific region or supply chain segment (e.g., biofuel or SAF certificates for logistics and transport).

We support the use of chain of custody and book-and-claim systems as long as they are based on robust safeguards and integrity principles in the traceability systems. In this regard, we encourage the use of decentralized systems based on synchronized or open databases, as opposed to having several centralized siloed book-and-claim systems as we currently observe in the areas of low-carbon fuels used in transportation.

3.2/ On the use of Carbon Credits

SBTi recognizes that “practices surrounding the use of carbon credits vary widely, leading to diverse outcomes and impacts and potentially requiring much more nuanced claims”. SBTi views the use of carbon credits mainly in two cases:

Compensation Claims: this suggests that purchasing carbon credits is equivalent to reducing the emissions the organizational boundary or value chain of a company, which is the basis for offsetting.

Contribution Claims: Indicate support or funding for climate actions outside the company's value chain, without implying a direct reduction in the company’s own environmental impact in its inventory.

In general, the SBTi standards require that carbon credits are not counted as emission reductions toward the progress of companies’ science-based targets. They can be used, as described early, under certain circumstances to support the neutralization of residual emissions or in Beyond the Value Chain Mitigation.

The Ecosystem Marketplace report from 2023 suggests that 59% of buyers in voluntary carbon markets have reported year-on-year decarbonization success. Buyers are also 1.3 times more likely to have established supplier engagement strategies and spend 3 times more on emission reductions activities compared to non-buyers on average.

The paper discusses another scenario in which “carbon credits from mitigation activities within the value chain are used to substantiate value chain emission reduction claims whenever they represent emissions abatement from activities traceable to the company's value chain. Such credits would be accounted for in a way that can be fungible with corporate GHG emissions inventory” (SBTi, p.13).

WWF and the NewClimate Institute explain that carbon credits are applied solely to support assumptions for calculating emissions inventories in this scenario. This can be useful when interventions with specific suppliers are challenging to account for through conventional methods. SBTi announced that the credits are not intended to provide flexibility for market-based accounting.

Our perspective:

We are aligned with the general climate community opinion that carbon credits, both for neutralizing residual emissions and for BVCM must come from high-quality interventions based on robust criteria and verification for quantification, permanence, quality, and additionality. We see great demand to develop and fund projects aligned with these criteria, as there currently are insufficient solutions to meet global decarbonization needs.

When considering the use of carbon credits from mitigation activities within the value chain, we agree that the industry will benefit from clear SBTi guidelines for their application to ensure consistency.

We support the development of educational material and guidebooks with best practices, case studies, and clear allocation of credits could help to ensure that the correct entities benefit.

Furthermore, guidance for transparent communication on the use of credits is crucial to avoid misleading claims.

We encourage the development of secure traceability systems such as blockchain platforms as measures to prevent double use, double claiming or double counting, which risk integrity and trust in the development of the carbon market.

We recommend SBTi to consider pragmatic Scope 3 approaches such as the VCMI’s Scope 3 Flexibility Claim, as long as they don’t distract companies to take immediate action in their own reductions as a priority.

In this proposed model, companies can offset up to 50% only of their gap in their annual Scope 3 reduction targets as a transition measure until 2035, “as long as it has already taken other steps to reduce its current emissions” (VCMI) provided that they have focused on in-value chain decarbonization as a prerequisite.

We believe that emission reductions and carbon credits must be accounted for and disclosed separately, similar as double reporting done under Scope 2.

We see an urgency to increase investments and efforts to scale the carbon removals sector in order to be able to meet future neutralization needs.

We strongly support the need to invest heavily in the development of high-quality and high-integrity projects aligned with SDG targets and quality standards, such as the ICVCM’s Core Carbon principles. In this context, projects with co-benefits (e.g. for biodiversity and local communities) should be prioritized.

Thinking beyond SBTi

We encourage businesses not to wait for SBTi and others to tell them exactly what to do before taking action. There is no universal "instruction manual" for corporate climate action, nor is it likely that there ever will be. Striving for perfection can hinder progress, and we cannot afford to delay.

It is unrealistic to expect voluntary initiatives like SBTi to anticipate and address every possible current and future corporate activity. Companies must be transparent and proactive in driving their own meaningful climate strategies.

At the same time, we acknowledge that without systemic, across the board, enforced, mandatory regulations we will not solve the climate crisis (or: the biodiversity one). Your voluntary action is essential beyond ambitious regulations.

Hence, our message is clear:

Reduce your emissions as fast as possible, and – not or – invest in high-integrity environmental projects within and beyond your operations. While committing to net zero in the future is important, taking responsibility for your ongoing emissions – today, tomorrow, and next year – is just as crucial. Shouldn't you be addressing those emissions now as part of your path to a low-carbon future?

Every business should take responsibility for their current impact by financing climate projects now – no matter if it counts for balancing out carbon footprints or not.

______

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay up-to-date with essential carbon market developments and exclusive announcements