COP30 in Brazil: 6 Take-Aways

Reading Time: 9min

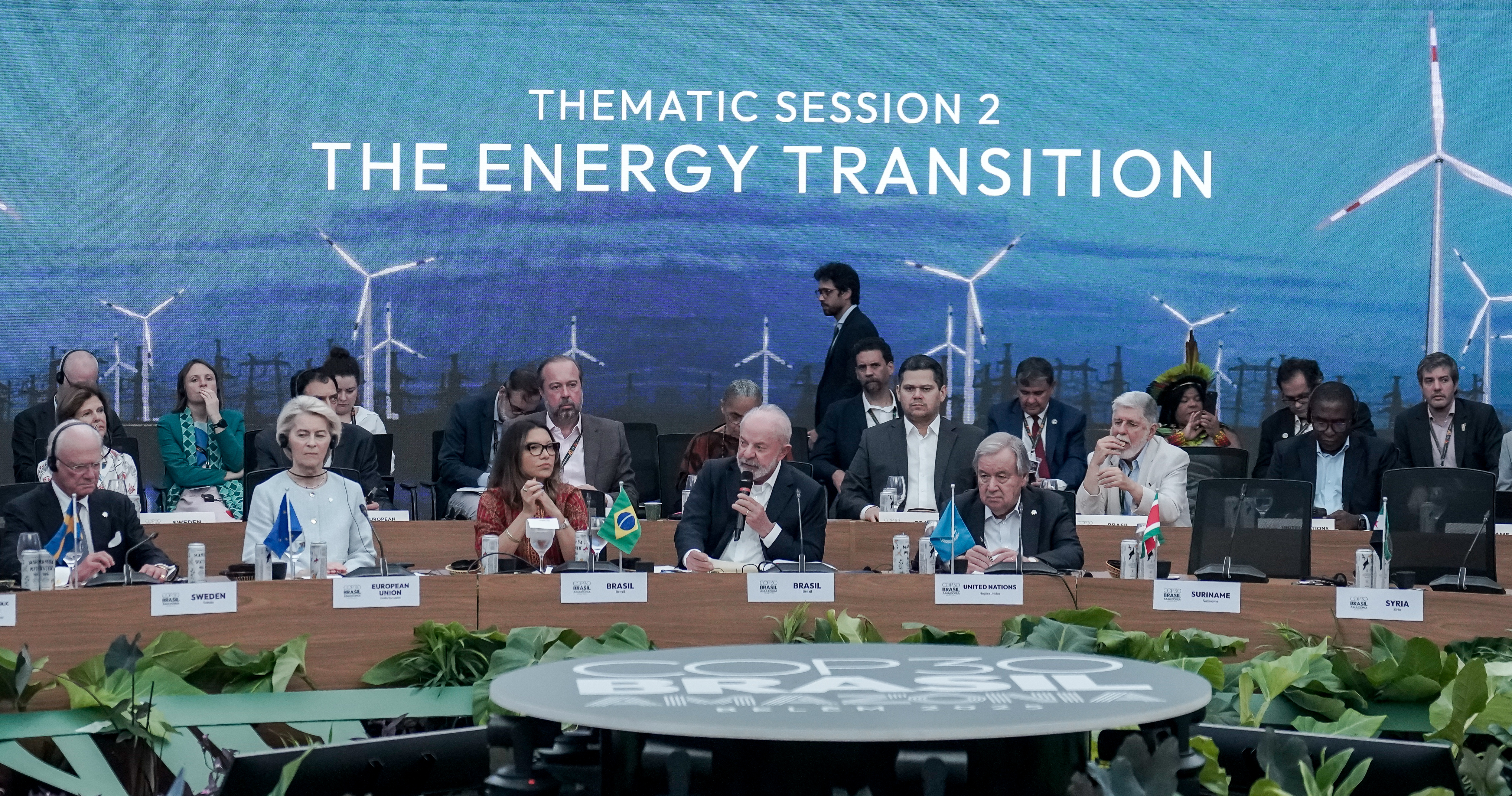

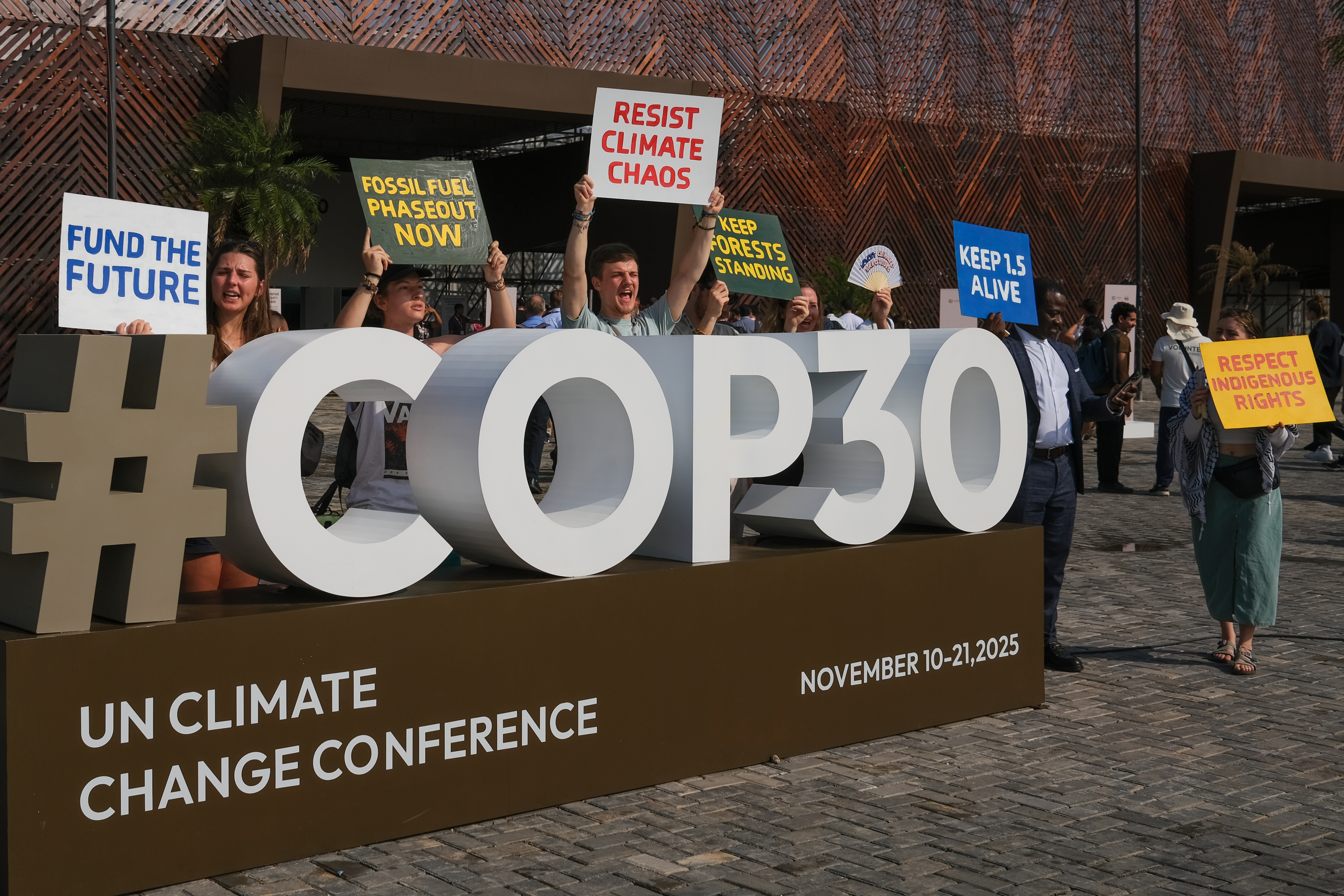

COP30 in Bélem, at the heart of the Brazilian Amazon delivered some of the strongest signals yet for forest protection, sovereign carbon markets and climate finance.

At the same time, the summit exposed a structural challenge: the world continues to rely on land-based carbon removals at a scale that is not feasible, while deforestation remains high and long-term climate targets remain incomplete.

For investors, policymakers and project developers, COP30 revealed a dual reality, remarkable progress paired with uncomfortable truths.

COP has been unable to deliver what we need most: a clear commitment to phase out of fossil fuels. To add insult to injury, a COP hosted in the Amazon also failed to propose a deforestation roadmap.

1. Progress on Paris Agreement Crediting Mechanisms (PACM)

About Article 6 and PACM

The Article 6 of the Paris Agreement is essentially the rulebook for how countries can trade and use carbon credits to help meet their national climate targets (NDCs).

Article 6.2 (the Direct Trade Route)

Think of this as a government-to-government exchange. It allows one country (the seller) to sell verified carbon reductions (called ITMOs) directly to another country (the buyer).

The most important rule here is "no double counting." If the seller country sells a credit, they must subtract it from their own climate achievements, ensuring the credit only counts once towards the buyer’s NDC goal. This makes it safe for countries to trade reductions.

Demand for internationally transferred mitigation outcomes (ITMOs) is estimated at around 200 million tonnes by 2030, based only on the submitted NDCs so far, reflecting growing confidence in cross-border crediting.

Article 6.4 (the Global Standard Route)

This creates a new, high-integrity, UN-supervised marketplace for project-based carbon credits (like credits from a specific wind farm or reforestation effort).

This mechanism sets a global quality standard to attract private investment. The resulting credits can be bought by countries to count toward their NDCs.

This rule is crucial because it ensures these new project credits are credible and helps funnel investment into climate projects around the world.

The World Bank estimates that NDC cooperation could cut up to 5 billion tonnes of emissions annually by 2030.

It could also unlock around $250 billion in climate finance each year, giving investors a clear way to support credible carbon projects.

Demand from the EU will add up to this, but this may only occur for the 2040 plan with most demand in the 2036-2040 period.

We wrote a Blog Post detailing Article 6 here and the inclusion of Article 6 credits in the EU here.

COP30 decisions on for Article 6

The Parties have long negotiated about minor updates to the mechanisms of Article 6. While progress has been made, more remains to be discussed in 2026.

On Article 6.2, there are only a few rules since it is mainly a country-to-country matter. However, the article mandates that countries submit "initial reports" about their bilateral carbon transactions, which are then subject to a "technical export review."

Reviews for the first six countries—Ghana, Guyana, Suriname, Switzerland, Thailand, and Vanuatu—have been completed.

Negotiations in Belém focused on demands for greater transparency and detail in this reporting and review system.

This urgency stems from the fact that expert reviews have, to date, found "inconsistencies" with submitted Article 6.2 trades.

Regarding Article 6.4, five core standards shaping credibility across sectors are now operational: Baselines, Additionality, Leakage, Suppressed demand, and Non-permanence & reversals.

The one on permanence was fiercely debated recently in the sector. It dictates how to deal with the risk that stored carbon – which was initially removed from the atmosphere and sold as a carbon credit – might be prematurely re-released, a scenario commonly referred to as a "reversal."

The first Article 6.4 Methodology (Landfill Gas Flaring & Utilisation) is now adopted, showing how the new standards translate into practice.

Nature-based projects, particularly forest restoration and carbon removals, are unlikely to see new methodologies approved in 2026, signaling a slower pace for environmental initiatives.

More debates around the next steps for #permanence will happen at the Supervisory Body in 2026. There are key items on the agenda, such as the reversal risk tool.

The new texts are available here:

Article 6.2: https://unfccc.int/documents/654647

Article 6.4: https://unfccc.int/documents/654826

Financial resources in the amount of $26.8 million will be transferred from the Clean Development Mechanisms, the carbon crediting scheme under Kyoto Protocol which is now being replaced by the PACM, to fund the startup and operations of Article 6.4, with an additional $5 million potentially allocated for capacity-building to ensure developing countries can participate effectively.

For existing CDM carbon credit projects, the door to the new market is staying open longer: the deadline to transition to the higher standards of Article 6.4 has been extended to June 2026. The final date for all transfers and cancellations of the old CDM credits (CERs) is set for December 31, 2026, providing a definitive close date for the legacy system.

2. Forest Finance Breakthroughs

The biggest announcement came from Brazil with the launch of the $125 billion Tropical Forest Forever Facility (TFFF). The largest forest finance proposal ever introduced.

It’s designed to reward countries for keeping forests standing, the facility will be managed by the World Bank, rely on satellite verification, and reserve at least 20% of funds for Indigenous Peoples and local communities.

It has already won support from 53 countries, including 34 tropical forest nations. Brazil and Indonesia pledged $1 billion each, Norway committed $3 billion over ten years, and France, Portugal and the Netherlands added political support.

Forest nations also moved ahead with new governance structures. WWF and the World Bank announced an Indigenous-governed financial institution for Colombia, enabling communities to directly receive revenues from carbon credits, green bonds and sustainable ventures. In parallel, a new intergovernmental commitment aims to secure 160 million hectares of Indigenous land tenure, paired with the renewal of the $1.8 billion Forest and Land Tenure Pledge.

Colombia went further, declaring that its Amazon biome — 42% of national territory — will become a no-new-oil and no-large-mining zone, and invited other Amazon countries to join a wider alliance for biodiversity and forest integrity.

WRI Brasil contributed another piece of the puzzle through the Flora Fund, a blended-finance vehicle aiming to scale restoration and assisted natural regeneration by 2026, already half funded by Bezos Earth Fund, AKO Foundation and The Coca-Cola Foundation.

3. Sovereign Carbon Markets Gain Momentum

COP30 also marked a turning point for Article 6 implementation and sovereign-level carbon market activity.

Honduras and Suriname signed Letters of Intent with Deutsche Bank and the Coalition for Rainforest Nations to develop sovereign rainforest credits under Article 6.2 — a potential model for future government-to-government transactions.

17 countries among which Colombia, Singapore, Turkey, the UK as well as the European Union (EU) as a bloc formally endorsed the Declaration on the Open Coalition on Compliance Carbon Markets. This new, voluntary initiative, spearheaded by Brazil, is designed to significantly enhance government-level cooperation on regulated carbon markets around the world. The primary goal is to strengthen the integrity, transparency, and effectiveness of mandatory (compliance) carbon markets—such as Emissions Trading Systems (ETS) or Article 6 related instruments.

Indonesia and Gold Standard launched a digital MRV pilot covering eight developers and an expected 800,000 tCO₂e — part of a broader push by Gold Standard to lower certification costs and strengthen Paris alignment.

Indonesia also mentioned plans to launch an international roadshow to showcase its forestry credits to potential investors and buyers before the end of the year.

Brazilian institutions further signaled long-term commitment through ProFloresta+, a 25-year programme by Petrobras and BNDES to purchase 5 million high-integrity Amazon credits, supported by concessional financing.

The Inter-American Development Bank issued its first forest restoration guarantee and prepared mechanisms to mobilize up to $1.5 billion across Brazilian biomes.

4. Beyond CO₂: Methane, Mangroves & Loss and Damage

Climate finance at COP30 extended far beyond carbon dioxide. Brazil and the UK launched the Super Pollutant Country Action Accelerator, supporting 30 developing countries in cutting methane, nitrous oxide and HFCs. With $25 million committed and $150 million targeted, the initiative reflects the rising urgency of curbing short-lived climate pollutants.

The World Bank’s methane fund secured $234 million, while the Global Mangrove Alliance unveiled the Mangrove Catalytic Facility, a platform aimed at creating national pipelines of bankable blue carbon projects.

Meanwhile, the Loss and Damage Fund formally entered implementation, launching a first call for $250 million in proposals — a critical milestone after years of negotiation.

Corporate climate action also intensified. Inter IKEA Group announced a restoration programme in the Atlantic Forest as part of its $108 million global carbon removal portfolio, combining ecological restoration with FSC-certified plantations and local job creation.

5. COP30 Also Showed Hard Realities

The Land Gap

Despite these achievements, COP30 also brought a sobering scientific message.

The 2025 Land Gap Report revealed that national climate plans now depend on over one billion hectares of land for future carbon removals — more than the land area of China. At the same time, current deforestation trends suggest that 20 million hectares of forests could be lost or degraded annually through 2030.

This contradiction undermines global climate planning: countries are banking on land-based removals that cannot materialize while continuing to lose the forests needed to stabilize the climate.

The report points to deeper structural issues — from global finance to economic incentives — that keep many countries locked into extractive development pathways.

The takeaway is clear: land cannot deliver what current climate plans expect from it.

No Agreement of Fossil Phase-out

In the final days of the conference, more than 80 nations—led by the United Kingdom and the European Union—pushed for a strong COP commitment that included developing a "fossil fuel roadmap" and explicitly referencing a "fossil fuel transition" in the outcome document.

However, this push was blocked by over 100 other nations, resulting in no final agreement on adopting these explicit commitments. The nations advocating for the strong language represented only 7% of global fossil fuel production.

Colombia and the Netherlands announced during the day that they would host an international conference on the just transition away from fossil fuels next April.

6. Ambition Still Falls Short

The political landscape remains fractured. Over 80 countries have yet to submit their 2035 climate targets, leaving global projections at 2.6°C to 3.1°C of warming. The G77 + China, representing the majority of the world’s population, endorsed the Belém Action Mechanism for a Just Transition, while several high-income countries — including Japan, the UK and parts of the EU — declined to join.

The gap between forest nations’ ambition and wealthy countries’ caution remains one of the defining tensions of global climate politics.

Our Take at Planet2050

COP30 shows what is possible but also what remains unresolved yet.

It delivered historic progress across forest finance, land tenure, sovereign carbon markets, digital MRV and community-led financial institutions. These are foundational elements of a maturing climate economy. But the summit also exposed persistent gaps: unrealistic land-use assumptions, ongoing deforestation, slow policy cycles and inadequate climate targets.

Carbon markets will play a central role in bridging these gaps — but only if they are high-integrity, Paris-aligned and transparently monitored.

The next decade will be defined not by pledges, but by implementation.

At Planet2050, we remain committed to one mission: making credible climate impact investable at the scale the planet requires.

If you’d like to dive deeper into the current state of the carbon market, we’ve just released our new Survey Report together with CDR.fyi. It highlights one of the sector’s biggest challenges: how to finance durable carbon removal at scale.